When I finished my first novel, I knew better than to hope for success. The publishing industry is competitive, especially for marginalized authors who write about their lived experiences. Few writers strike gold on their first completed project.

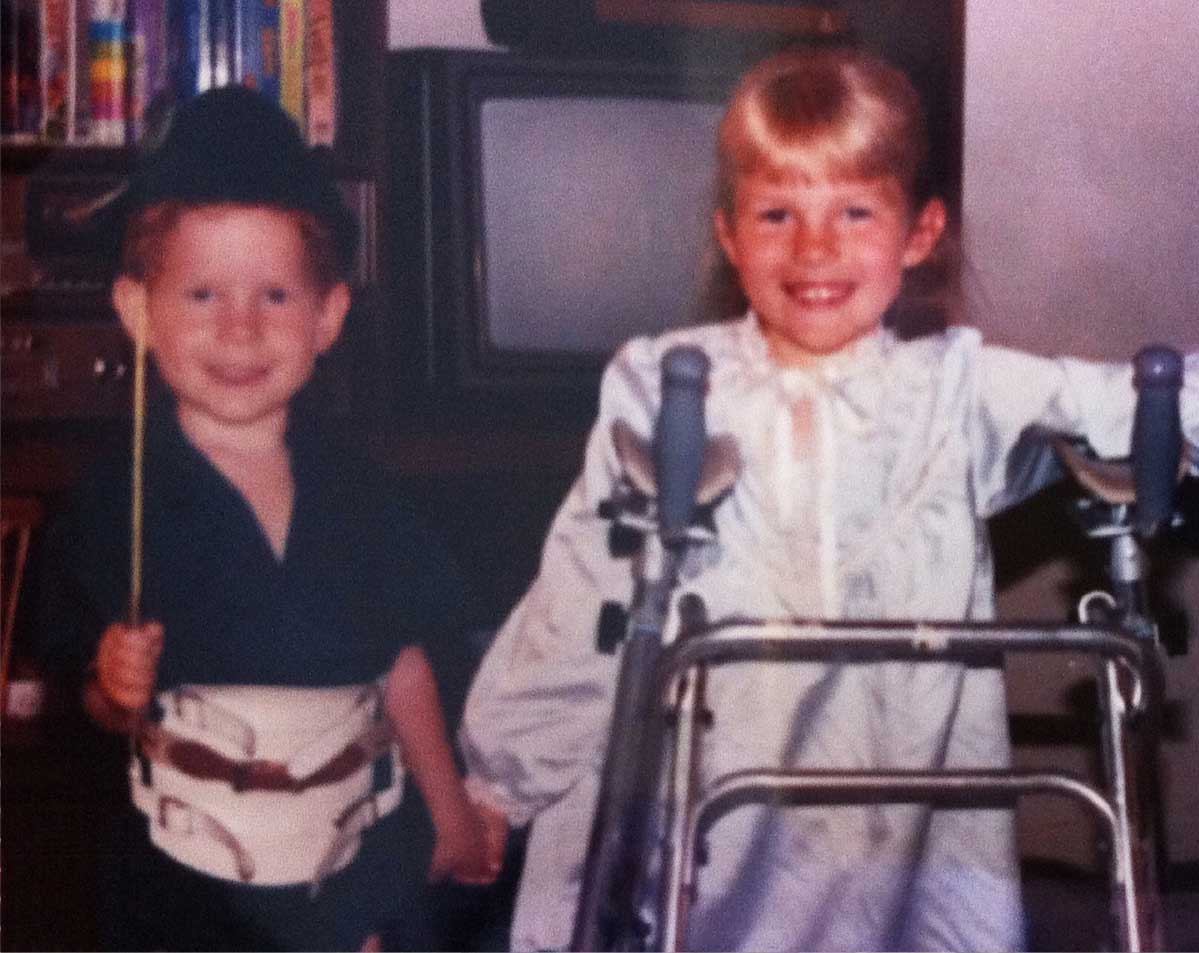

If you'd asked me at the time, I would have said I was prepared for failure. And I was! But that didn't stop the rejection from hurting. I love everything I write, but that book was especially important to me, as it featured the disability representation I'd wanted since childhood. It was the culmination of a decade of striving — and it went nowhere.

“But the truth is it did lead somewhere. That book taught me so much about writing, from the nitty-gritty of revision to the sweeping strokes of character and plot. More than anything, it clarified what I want to create in this life.”

The therapist in me recognizes the shift in mindset as the result of failure. If I hadn't abandoned my book, I wouldn't have questioned my purpose as a writer. I wouldn't have realized that, while writing is difficult, especially in a world that often devalues disabled perspectives, it is also worth it.

I wouldn't have rededicated myself to my craft or written a book that blew my previous one out of the water. Would it have been easier without the failure of rejection? Absolutely. But would it have been as meaningful? Probably not. And that — that's where the magic is.